2022 Summer Speaker Series: Tackling Environmental Challenges Through Sustainable Entrepreneurship

This summer, Bethesda Green’s Innovation Lab is once again bringing together founders, industry experts, and policy makers for a series of conversations that will inspire and educate all who attend.

During our 2022 Summer Speaker Series, 12 industry experts are coming together to discuss the impact of required climate related financial disclosures, and some of the key challenges and opportunities facing our food system.

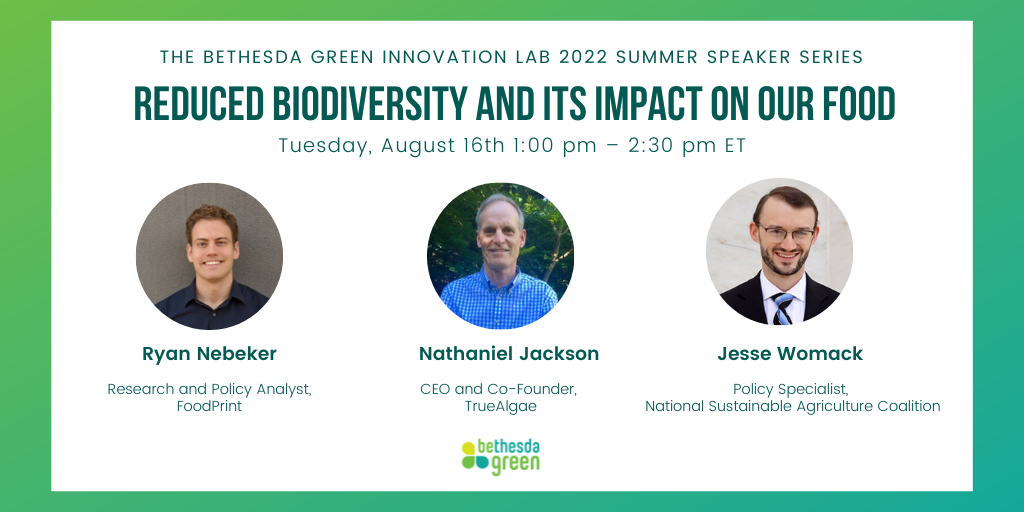

The following is a summary of the final session hosted on Tuesday, August 16th. Watch the recording here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UkVGkkyKxbg

Panelists

- Ryan Nebeker: Research and Policy Analyst, FoodPrint

- Nathaniel Jackson: CEO and Co-Founder, TrueAlgae

- Jesse Womack: Policy Specialist, National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition

During this session we brought together a panel of experts to discuss the impact of reduced biodiversity on our food systems, and how all of us, not only the agricultural community policymakers, must work to preserve it. Ryan Nebeker is the Research and Policy Analyst for FoodPrint, an educational nonprofit that aims to help people understand where their food comes from and how our food system impacts people, animals, and the environment. Nathaniel Jackson is the CEO and Co-Founder of TrueAlgae, a company that produces an organic and proprietary soil amendment booster containing useful metabolites that are expressed in the cultivation of algae in vertical photo-bioreactors. Jesse Womack is a Policy Specialist for the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition. Below, please find a collection of some of the key takeaways from this session.

Background

Farms are ecosystems, and it all comes down to the soil. These delicate ecosystems have so far demonstrated some resilience against growing commercial agricultural pressures, but the impact of climate change, bringing its increasingly severe weather, is testing that resilience.

Scientists estimate that there are 8.7 million different species of plants, animals, and microorganisms that are defined by the term biodiversity. To put it simply, biodiversity is everything around us. Every form of our biodiverse system performs specific purposes that are critical for maintaining life on Earth.

There are two types of biodiversity that are important to understand when discussing agriculture. Ryan Nebeker, from FoodPrint, noted the difference between Wild Biodiversity – the life that exists in an agricultural space and the way that agriculture has an impact on it – and Cultivated Biodiversity – the organisms that are grown for agricultural production. Soil is the easiest example of the interplay between wild and cultivated biodiversity, because soil itself is living, but then humans embed the crops we farm into that natural system.

Industry and Environmental Pressures Affecting Biodiversity

The various industry and environmental pressures affecting biodiversity, according to Jesse Womack from the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition, stem from issues associated with monoculture. Within the United States we often see the agriculture industry view specialization as the most efficient and profitable method of production. A majority of the arable lands have been developed to support simplified monoculture production of corn and soybeans, at a direct cost to biodiversity within the soil and in the wildlife nearby. Other industry pressures include those related to regulation that favors simplification and market fluctuations, both in high input costs and changing produce prices. On the regulation side of the equation, Womack expanded on nitrogen policy differences between the US and Europe, where only certain US states are restricting nitrogen usage, but Europe is phasing out nitrogen completely.

The environmental pressures affecting biodiversity relate to monoculture systems as well. Monoculture farms are increasingly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, such as floods or droughts. These environmental pressures further complicate the challenges involved in switching to a different system of agriculture that would not rely solely on one crop. Nathaniel Jackson, the CEO of TrueAlgae, mentioned that the persistent use of chemical and synthetic fertilizers, which leads to impoverished soils requiring more nutrients, abiotic stressors from climate change, and the lack of naturally occuring nutrient availability are some of the other environmental pressures degrading the biodiversity in soil.

Preservation of Biodiversity

Biodiversity is the cornerstone of every functioning ecosystem, including those that supply oxygen, clean water, and pollinate our food. To maintain life on Earth, we must preserve biodiversity in our agricultural systems. To do so, there must be a combined effort from the agricultural technology sector, the government and legislative bodies, and the farmers themselves.

The agricultural technology (AgTech) sector has seen recent expansions in funding opportunities and an increased need for improvements due to extreme weather conditions, making this an exciting space for entrepreneurs. One example of this is TrueAlgae, a company that produces high-quality microalgae and byproducts for agricultural applications. Jackson explained how TrueAlgae’s product, TrueSolum, is an organic soil booster that increases microbial health and reduces the need for fertilizers. This product is a direct solution to some of the outlined environmental factors affecting biodiversity. With more attention given to the AgTech industry, farmers can expect useful solutions to critical problems.

Another technique used to address some of the agricultural industry’s critical problems is through the practice of Sustainable Agriculture, which involves methods that allow farmers to meet society’s present food needs, without compromising the ability for future generations to also meet their needs. Nebeker explained that most sustainable agriculture practices are focused on increasing biodiversity within the soil. These practices include modified tilling that decreases the amount of nutrients lost, increased cover cropping to allow for the soil to stay in place, and regenerative agriculture through the use of animal manure as a natural fertilizer. On top of these, our panelists stressed the importance of diversity in what is grown, which helps with both decreasing the likelihood of diseases that can knock out your whole crop and decreasing the effects to biodiversity from monoculture systems that stifle microclimate growth. Nebeker suggested farmers cultivate wild biodiversity and cultivated biodiversity interaction by increasing the edge zone surface area on their fields, the area where cultivated biodiversity often meets wild biodiversity. While each of these sustainable agriculture practices are leveraged to work, they take time, especially in areas like soil health, which can require 5-9 years to see true progress. Both the durability and permanence of the adoption of sustainable agriculture practices are key to increasing biodiversity and its benefits.

The US federal government continues to support farmers through legislative priorities, and in recent years, has increased the attention given to our farming communities. Womack pointed out, however, that current policies exclude the idea that conservation practices must be layered, despite some agencies stressing the importance of deploying multiple techniques at once. The Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS), a non-legislative portion of the US Department of Agriculture, is one of the agencies that encourages farmers to employ multiple methods of conservation at once. The NRCS recommends four main principles of soil health; maximize presence of living roots, minimize chemical disturbance, maximize Soil Cover, maximize biodiversity. By diversifying the cover crop and cash crop species, farmers can ensure that their soil remains healthy and undisturbed throughout the seasons. The Conservation Stewardship Program, from the NRCS, is the only conservation program that encourages farmers to plan for 5-year intervals, accounting for the whole scope of the farm, while also funding new practices and any enhancements made to those practices over time. One recent piece of legislation, the Inflation Reduction Act, included $20 billion in funding for conservation reduction programs, most of which will go to large-scale farmers to cover the costs of purchasing and planting cover crops, as mentioned in this VOX article. As Womack pointed out, any layering of conservation techniques is missing from this new legislation as well. The Farm Bill, which encompasses most of the Federal government’s agriculture policy, is up for renewal in 2023. The Local Agriculture Market Program (LAMP), created during the previous Farm Bill authorization period, advocates for funding to be directed to smaller sized farms that produce food for direct human consumption. Womack voiced his support for LAMP, as attention to small farmers is another key piece that is often missing from agricultural policy. By stressing the importance of layering conservation techniques, not solely cover-crop funding, and including additional programs for small-sized farms, policy makers can support the preservation of biodiversity in agriculture.

Conclusion

In summary, we asked our panelists to expand on the ways in which consumers can influence sustainable agriculture, especially in their local communities. Nebeker encouraged consumers to look for sustainable food labels when purchasing items. Specifically, the USDA Organic label tends to be the most strict on the growing side and widely available on the consumer side. Organizations have Good Food purchasing programs that guide consumers and institutions to buy equitable and sustainable food. Womack suggested that consumers stay engaged politically and act locally by getting involved with their area school districts and motivating them to buy sustainability. By propping up institutional buying power, it brings more attention and credibility to the need for sustainably grown foods.

Finally, our panelists shared their closing remarks on biodiversity and the impact on our food system. Jackson discussed the cyclical nature of biodiversity and food. A diverse microbiome in the soil leads to healthier foods and healthier bodies. And in the opposite direction, with reduced biodiversity, there’s an extreme negative or unhealthy cycle. Womack added to this statement with a country wide perspective, noting that our agricultural system and the country becomes more resilient with increased biodiversity. Nebeker closed with the thought that there is hope for change, especially since changes have been made before. Indigenous people have been stewards of biodiversity protection for years, and the sustainable agriculture techniques encouraged today have proven reliable to their populations.

Find sustainable foods here:

- https://foodprint.org/eating-sustainably/food-label-guide/

- https://www.montgomerycountymd.gov/agservices/farm-to-table.html