Racism in the Air We Breathe

By Jordan Lee, Bethesda Green B Corp Intern

Following the murder of George Floyd by a White police officer, Floyd’s final words “I can’t breathe” became a rallying cry across the nation against police brutality and systemic racism. The words “I can’t breathe” are emblematic not only of police brutality, but also of another poignant way systemic racism plagues society: through the air that Black and Brown communities breathe.

COVID-19 has exacerbated the deadly effects of this inequity. Black and Brown people are dying from the respiratory virus at disproportionate rates. The Trump Administration, health experts, and mainstream media alike have attributed higher death rates to pre-existing health conditions among African Americans. But the question we should be asking is why do these pre-existing health conditions exist in the first place? We must examine the overwhelming role of racism. Racism affects people’s quality of healthcare, job opportunities, and the environment in which they live.

Environmental racism refers to the ways pollution and climate change disproportionately affect people of color. Race is the number one predictor of whether a person lives near toxic waste. Studies found this was the case in 1987 and worsened over the subsequent twenty years. People of color continue to face disproportionate exposure to air pollution today, and we can certainly find examples of systemic environmental racism right here in Montgomery County.

Numerous studies have documented the negative health outcomes that result from repeated exposure to certain toxins and pollutants. The EPA specifically lists premature death, heart problems, aggravated asthma, decreased lung function, and increased respiratory symptoms. Other studies have linked pollutants from landfill and waste sites to cancer.

Even though, Black communities and communities of color suffer disproportionately from pollution and waste, studies have shown that white people disproportionately contribute to pollution through their consumption of goods and services. We must understand environmental racism and how it functions within our urban environment, in order to build a more sustainable world.

Environmental Racism is Systemic

Environmental inequities are not random. Environmental racism is tied to the long history of residential segregation in this country and the systems set up to economically and politically disenfranchise communities of color. But environmental racism is not a thing of the past; it continues to be systemic, deliberate, and pervasive today.

There is a long, well-documented history of the government, financial institutions, and individual white communities intentionally constructing racially segregated communities through various policies and practices. Such policies and practices include, planning and zoning laws, redlining and discriminatory lending practices, racially restrictive covenants and more.

In the 1930s, the federal government rated neighborhoods to help mortgage lenders determine which areas of a city were considered “higher-risk investments.” The federal Homeowners’ Loan Corporation created color-coded maps, with red representing “hazardous” neighborhoods. Black neighborhoods were labeled red, regardless of household income. One Black person in a neighborhood could lead to redlining of the entire neighborhood. This became known as redlining.

Redlining not only affected Black people’s ability to own property but also determined government designations for land use. In red, predominantly Black and immigrant neighborhoods, it was difficult to get a home loan. In green, predominantly White neighborhoods it was easy to get a loan. From 1934-1968, White families received 98 percent of home loans, giving them the opportunity to build wealth. Receiving less than 2 percent of home loans, most Black and immigrant families did not have this same opportunity.

The historical lack of investment in Black neighborhoods has meant lower property values, making it cheaper for industry, corporations, and government to buy land to use for factories, waste facilities, and production plants in these neighborhoods. Through zoning and land use laws, the government has actively permitted industry to pollute these neighborhoods.

Industrial land use keeps property values in these areas low, making it difficult for people to build enough wealth to move away. Lower property values also meant the people moving into the area are likely to be lower income, a factor that is linked to race.

Local Examples of Environmental Racism

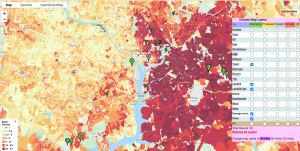

Image Caption: Earth Justice Network’s Environmental Justice Map

Image Caption: Earth Justice Network’s Environmental Justice Map

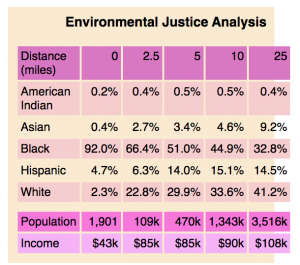

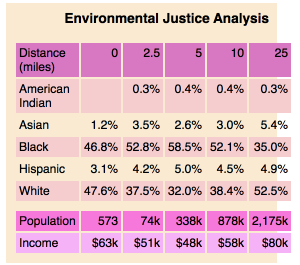

We don’t have to look far to see environmental racism at work; just look at DC’s waste management. The DC area is among the most segregated in the United States, with a high concentration of Black people on the east side of the city and high concentration of White people on the west side. The trash transfer stations in D.C. displayed on the map above– Federal IPC, Fort Totten, and Benning Road, Rodgers Brothers C&D, and WMI Northeast – are all located on the eastern side of the city, surrounded by majority-Black communities. The Earth Justice Network’s community map shows the racial and socio-economic make-up of communities surrounding waste facilities across the country. Of the five major transfer stations located in D.C., Black people make up between 63% – 85.2% of the population living within a 2.5-mile radius of these trash facilities, respectively. The tables below show that the average household income within the surrounding neighborhood of the Federal IPC and Benning Road transfer stations is in both cases, well under the D.C. average household income of $82,600. The percentage of Black people gradually decreases as the distance from the waste sites increases.

Image caption: Energy Justice Network’s Environmental Justice Analysis of the Federal IPC (left) and Benning Road (right) waste transfer stations.

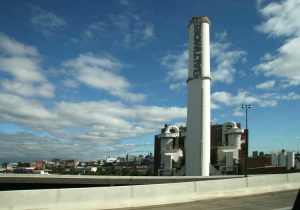

Image Caption: The Baltimore Incinerator, Source: Ivy Dawned Flickr

Image Caption: The Baltimore Incinerator, Source: Ivy Dawned Flickr

Another example of environmental racism is the Wheelabrator trash incinerator in Baltimore. It is the city’s largest single source of air pollution and produced 82 percent of the sulfur dioxide and 64 percent of the nitrogen oxides emitted by smokestacks within city limits in 2014, according to the EPA. Of the population living with a 2.5-mile radius, 58.2 percent are Black.

Image Caption: Energy Justice Network’s Environmental Justice Analysis of the Baltimore Wheelabrator Incinerator

Image Caption: Energy Justice Network’s Environmental Justice Analysis of the Baltimore Wheelabrator Incinerator

The State of Maryland is complicit, and even facilitates environmental racism. A Maryland state law allows trash-to-energy incineration to be essentially counted as renewable energy, despite protests from environmental activists. As a result, the incinerator was able to collect roughly $10 million in green energy subsidies from 2011-2017.

In both the D.C. area and Baltimore, communities of color have been on the frontlines of fighting against proposals for new incinerators, which has ultimately benefited everyone. And although people of color are more likely to be affected by environmental racism, White and wealthy communities have historically benefited from and perpetuated racist systems, and therefore also have a responsibility to play a role changing these systems.

What Can We Do About It?

Image Caption: March to stop a new incinerator in Baltimore.

Image Caption: March to stop a new incinerator in Baltimore.

To reiterate, environmental racism does not happen in a vacuum. The government both created land use laws that allowed chemical plants, production factories, and general industry to pollute the land and failed to regulate industry in Black and Brown communities. A 2015 study found that the EPA denied 95 percent of the civil rights claims communities of color brought against polluters.

While our individual actions such as reducing our own personal waste and consumption continue to be important, we cannot lose sight of the systemic nature of this problem. We need policy, we need regulations and protections, we need legal mechanisms through which people can protect their communities — all of which are all currently under attack by the current Trump Administration.

So, what can we do? Educate ourselves about issues of environmental racism happening in our own communities. In Montgomery County, hold local elected officials accountable and contact state and local representatives to support the Zero Waste Initiative in Maryland. Get involved in fighting for cleaner air and water.

Vote for candidates up and down the ballot , like Joe Biden, who have a climate action plan that incorporates environmental justice. Vote Trump out in November.

Support national environmental justice organizations, like The Climate Justice Alliance, Energy Justice Network, and Communities for a Better Environment.

As environmentalists, we also need to build a movement that is more inclusive. The environmental movement cannot just be about protecting nature and animals. Justice for all human beings must be at the core of our work. We should acknowledge the racist history of the environmental movement and address the whitewashing that continues to take place. As environmental justice continues to gain traction within mainstream environmentalism, we must also acknowledge the work that Black and Indigenous, and other People of Color have been doing for decades, even centuries, to protect the environment and build an inclusive movement. It is imperative to ensure that we are adopting a framework of environmental justice and intersectional environmentalism to truly support all people and the planet.